NO SIGNATURE NEEDED

NO SIGNATURE NEEDED

Where would today’s jewelry designers be without Suzanne Belperron? It is no exaggeration to call her the most influential woman of jewelry design. She has also been called elegant and audacious, her jewelry labeled both “brilliant” and “barbaric.” According to Karl Lagerfeld, an avid Belperron collector, “There’s no one else like her.”

Belperron joined the house of Bovin in 1919 at age 21, where her curvaceous designs deviated from the geometric expressions of the Art Deco movement. She pushed volume to the limit while maintaining a sense of refinement. Her influence was so significant that it is sometimes difficult

to differentiate between her designs for Boivin and those she created after she left the company.

In 1932, Bernard Herz, a Parisian stone dealer, invited Belperron to design for his maison, where she was given free rein. She created organic shapes such as petals, fruits and seashells, as well as Egyptian, African, Indian and Asian motifs. She daringly set precious stones in carved rock crystal, chalcedony or agate, and even wood and ivory. She chose materials for their beauty, not their value. Like her former mentor Jeanne Boivin, Belperron refused to sign her pieces, stating, “My style is my signature.” Her name, nonetheless, gained fame as her pieces were featured in Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar and adorned the most fashionable women of the day, including the Duchess of Windsor, Princess Aga Khan, Daisy Fellowes, Diana Vreeland, Josephine Baker, Colette and Elsa Schiaparelli, who declared them “the new theme in jewels.” She even made jewelry for Marie Munn, a blind pianist – a testament to the tactile beauty of Belperron’s forms.

Bernard Herz was of Jewish origin, so Belperron took full control of the company in November 1940 to ensure its survival during the Nazi era. But in November 1942, she was arrested for concealing a Jewish business. During her transfer to the Gestapo headquarters in Paris, Belperron allegedly swallowed all the pages of Herz’s address book, one by one. Bernard Herz was arrested the same day at his home and sent to an internment camp, from which he sent a letter entrusting his and his children’s affairs to Belperron. Herz ultimately died at a concentration camp. Despite this tragedy, Belperron managed to maintain the business during the Occupation. Her originality kept the firm on the cutting edge until her retirement in 1975.

YOUNG GENIUS

YOUNG GENIUS

Once in a great while, there appears a contemporary designer whose creations are remarkable enough to share the spotlight with Fred Leighton’s

collection of historical and famous maker jewels. Lauren Adriana, a young London-based graduate of Central Saint Martins, has achieved this feat

with her audacious, imaginative designs.

Adriana established a singular aesthetic, prodigious reputation and loyal clientele by age 30. It’s not surprising considering how long she’s been

cultivating her passion. At age five, she ogled the gems at London’s Natural History Museum and used her pocket money to buy polished pebbles

in the museum shop. By age 12, she was shopping London’s New Age markets for cut gemstones. When she was 15, Adriana found a book about

American jewelry house Verdura, which inspired her to learn to paint her own jewelry designs in gouache.

Today, Adriana still begins each piece with a painting, then oversees every step of the creative process to ensure that the final result looks exactly

like the painted design. Her daringly glamorous pieces feature gemstones in unusual hues, set in glimmering discs or spiky, sparkling shapes.

Some take cues from classical styles; others seem imported from a distant galaxy. “I believe a jewel has to be forward-looking, building on what’s

gone before, but not relying on motifs or narratives from the past,” says Adriana. “My aim is to create a jewel that reaches beyond the time you’re

in.” Lauren, consider your aim achieved. These creations are wildly coveted now, and are sure to be collectible in future eras.

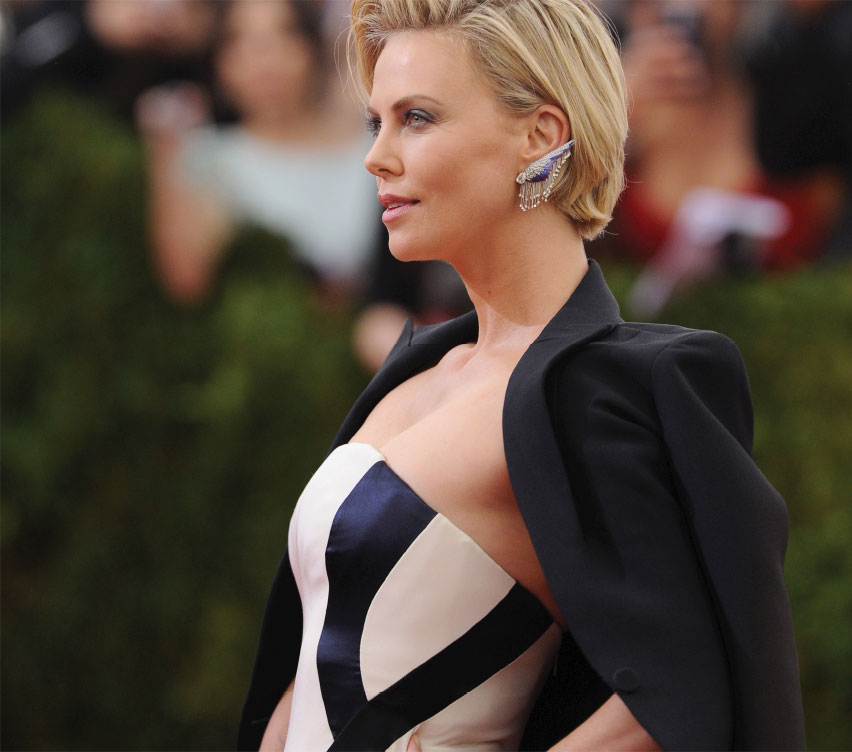

ACADEMY AWARDS 2015